Veteran Lynch would relish one more trip to Qualcomm.

By JOEY JOHNSTON

Tribune Staff Writer

(c) Tampa Bay Times. Originally published Jan. 14, 2003.

Sometimes, he will lie awake at night, thinking about the dream. It’s nearly reality.

One more game.

One more victory.

That’s all it takes now.

If the Bucs defeat the Philadelphia Eagles in Sunday’s NFC Championship Game, the franchise earns its first trip to the Super Bowl.

And John Lynch, Tampa Bay’s All-Pro strong safety, becomes the homecoming king.

“It’s almost too much to hope for,” Lynch said. “It’s hard not to imagine what it would be like. But you can’t even look that far ahead. There’s still business to take care of.”

Super Bowl XXXVII will be held at San Diego’s Qualcomm Stadium, where Lynch attended his first Chargers game at age 2. He saw practically every play of Air Coryell. He remembers the Charger fight song. He can close his eyes and envision the precision combination of Dan Fouts to Kellen Winslow.

His ears still ring from that Saturday night in 1984, when the stadium shook and Steve Garvey’s ninth-inning playoff home run rescued the Padres and put them within a game of the World Series. He probably witnessed Tony Gwynn decorating every square-foot of the outfield with a base hit.

How many times has Lynch been in that stadium? Hundreds?

Once more would be a dream come true.

Maybe that’s not too much to ask. After all, Lynch, who was raised just up the coast at Solana Beach, has made a career out of fulfilling his greatest desires.

He’s 31, the senior Buccaneer, one of only five remaining players to wear those orange creamsicle uniforms and helmets with the winking-pirate logo. When he arrived in Tampa Bay in 1993, choosing the NFL over a burgeoning pitching career with the Florida Marlins’ organization, perhaps he was a bit naive.

“I knew the Bucs hadn’t had much success, but I was always an optimist,” Lynch said. “I thought we were going to win and everything was going to be great.

“But I look back now and think, “Wow, we really had no chance.’ It was pretty bad. The goal was to play .500 ball. And we kept falling short of that. Me? I couldn’t even start. I could barely get on the field at times. So yeah, there were times when I questioned, “Hey, what am I doing here?’ “

Now it’s hard to imagine the Bucs without John Lynch.

He has developed into the signature player at his position. Along with fellow cornerstones Derrick Brooks and Warren Sapp, he has helped transform Tampa Bay’s defense into the NFL’s No. 1 unit. He was recently voted into his fifth Pro Bowl.

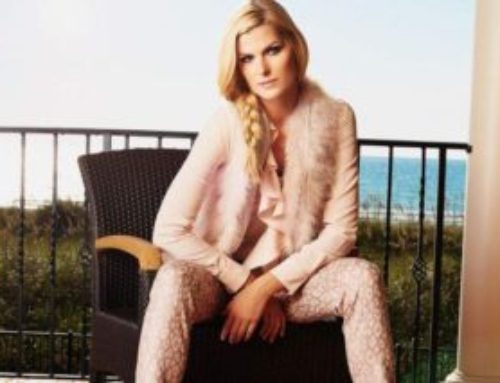

He’s married to the love of his life, Linda, who last month gave birth to their third child. Nearly three years ago, Lynch and his wife formed the John Lynch Foundation, which rewards local student-athletes with scholarships and develops young leaders through its various community programs.

Lynch is a finalist for this season’s Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year Award, the league’s highest honor for off-field contributions, which will be presented next week.

“I’m so very lucky,” he said. “There are definitely times when I believe I’ve been blessed and have it all.”

Well, almost.

One more game.

One more victory.

Setting The Example

Lynch’s No. 47 jersey has become synonymous with contact.

Crunching tackles.

Lynch once met Detroit’s Barry Sanders in the hole and shook him with a seismic blow, one the running back later said was the most explosive he ever had absorbed.

Bone-jarring hits.

St. Louis running back Marshall Faulk once caught the business end of a Lynch blitz. Faulk, who could barely see straight, popped to his feet, refusing to give Lynch the satisfaction, but he needed a road map to find the Ram huddle.

“When teams get off the bus, they’re already looking for where No. 47 is, believe me,” Bucs defensive coordinator Monte Kiffin said.

Bucs coach Jon Gruden marvels at the copycat defensive backs in college football who wear No. 47, all the John Lynch wanna-bes.

Perhaps they are taken by Lynch’s sheer impact, the savage one-on-one competition that remains a large reason for the NFL’s popularity.

Gruden and Kiffin? They revert to the practice field, where their oldest defensive back remains driven to the point of perfectionism. They think back to the meeting room, where wide-eyed rookies watch him ask questions and take meticulous notes.

“It’s second-and-nine and John has studied the tape, he recognizes the formation, so he knows it’s going to be a dropback pass, maybe a three-step drop,” Gruden said. “He sees it’s an inside route. He gets a quick jump. He takes the perfect angle. The headgear flies. That’s John Lynch.”

John Howell, Lynch’s second-year understudy at safety, remembers idolizing No. 47. When Lynch approached with tips during last season’s minicamp, Howell didn’t hear a word. He was in awe.

“Imagine that, taking the time to help some Podunk rookie,” Howell said. “He’d never big-time anybody. He’s what a pro football player should be.”

Lynch’s pride and controlled anger, which seem so evident on the field, are absent in other encounters.

John Lynch is approachable. He remembers your name. He cares. He’s a nice guy.

“There’s an aura to him,” cornerback Ronde Barber said. “He endears himself to people. He finds something in common with you and runs with it.”

“There’s truly no chance John Lynch’s name shows up in the Metro section of your newspaper,” Bucs general manager Rich McKay said, “unless he’s giving away money, presenting a scholarship or kissing a baby. Put it this way: As an ambassador for our franchise, he ain’t bad.”

When the comments of Barber and McKay are relayed to Lynch, you can practically detect a blush.

“The truth is, I’m really kind of a shy guy,” Lynch said.

Aggressive, Yet Gentle

You’d never believe that?

It’s a fact.

Three seasons ago, Lynch’s third-quarter interception against the Washington Redskins ignited a playoff victory, one that sent Tampa Bay to its last NFC Championship Game. It remains Kiffin’s favorite John Lynch moment. On the Tampa Bay sideline, with his team trailing 13-0, Lynch spiked the ball defiantly and yelled at his offensive teammates, challenging them to pick up the pace.

“I believe the words were something like, “We’re doing our part! Now you guys do yours!’ ” said Barber, who was standing nearby. “Everybody was like, “Whoa!’ Call it a coincidence if you want, but that’s when our offense finally drove for a touchdown.”

That same John Lynch was so frightened to ask a girl to his eighth-grade dance, he begged his outgoing younger brother, Ryan, to get on the telephone for him and pretend he was John. Ryan shrugged his shoulders. OK. The girl said yes. John had his first date.

Early in Lynch’s career, after a particularly brutal loss, he was nursing a headache on the plane trip home. Sapp, sitting a few rows behind, was playfully tossing some cards, one by one, intentionally hitting Lynch in the head. Please stop, Lynch said. Nope. Look, Lynch said, if you don’t stop, something’s going down between us, right here. Nope. Another card brushed Lynch’s head.

When Lynch bolted from his seat, it took about six teammates to restrain him. Sapp always liked his teammate. But now it was unflinching respect.

That same John Lynch was timid and hesitant in his early career. He was constantly dressed down by Bucs defensive coordinator Floyd Peters, who miscast Lynch as a linebacker. Lynch never was called by his name in 1993. It was always, “Hey, rookie.”

Perhaps it was intended for motivation. Lynch withdrew even more.

So there he was, unable to crack the lineup for one of the NFL’s worst franchises. He couldn’t see the tunnel, let alone the light. Some days, he really missed baseball.

One day at a golf tournament, Lynch was venting to Ronnie Lott, the eventual Hall of Fame safety. Lott, who was familiar with Lynch’s Stanford career, cut him short. “I’ve seen you play,” Lott said. “You can play at the highest level.”

“From that moment on, I decided no one would ever tell me I was no good,” Lynch said. “If I was going out, I was going out guns-a-blazing. That was a decision I made. It was a big one.”

But his real turning point occurred earlier.

It Was Destiny

Lynch knew Linda Allred at Torrey Pines High School, but she was two years older. Linda actually was much better friends with Lynch’s sister, Kara. In fact, they became roommates at the University of Southern California, where Linda played tennis.

In college years, John and Linda worked out together with the same personal trainer. But it was friendship, no more. John kept wishing he could meet a girl just like Linda. Then he could have a serious relationship.

By February 1993, Lynch had found his standard – Linda herself. They began dating and were engaged by July, just before Lynch’s departure for training camp. Lynch bought a ring, made an appointment to formally ask her father, then proposed on the beach at Del Mar.

“It was destiny,” Linda Lynch said. “It happened so quickly that we were both asking that night, “What did we just do?’ But I truly believe we were meant to be together. We are so close. I couldn’t ask for a better husband or father for our children.

“I competed in athletics. I have some idea of what he goes through. I know how much he wants this.”

Before each game, Linda writes John a little note, which he usually reads at the stadium. It’s an affirmation of belief or confidence. He’ll get another note Sunday. But those words probably don’t need to be written or spoken.

“We’re so close,” Linda said. “It’s in the back of your mind. To have it happen would almost be too good to be true.”

The Bucs in Super Bowl XXXVII. John Lynch, coming home to San Diego. The dream of a lifetime. And it’s almost reality.

Couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.