Rebecca Lobo, former women’s basketball legend, now is content raising her family.

By JOEY JOHNSTON

The Tampa Tribune

(c) Tampa Bay Times. Originally published Feb. 11, 2008.

One day after winning the national championship of women’s basketball, nearly 13 years ago, she was in New York, making late-night conversation with David Letterman. Later, she was summoned to Washington, where she jogged with President Clinton.

A Barbie doll was designed in her image, WNBA-style. She had her own line of Reebok sneakers.

Her college jersey hangs in the Basketball Hall of Fame. Her U.S. Olympic team jersey is in the Smithsonian, not far from Dorothy’s ruby slippers in “The Wizard of Oz.”

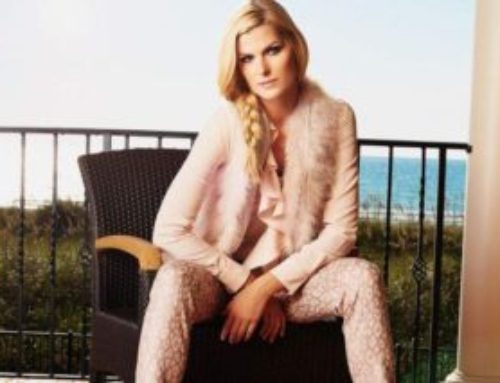

Rebecca Lobo, 6-foot-4 American icon, can’t fully explain what happened.

She never aspired to be famous. In a way, it’s still surreal. But that’s OK. At least she knows what is real.

Far from Connecticut’s Gampel Pavilion, Atlanta’s gold-medal stand and Madison Square Garden, Lobo has shifted into a new role, one she always wanted.

She’s a mom.

“I just love watching Rebecca mothering sometimes,” said Lobo’s own mother, RuthAnn, who draws prime babysitting duty. “Her eyes are filled with warmth and love. It just shines through. It makes me very proud.”

Lobo, 34, and her husband, Steve Rushin, an author and former Sports Illustrated writer, live in a small Connecticut town with their two daughters – Siobhan (3) and Maeve (18 months). Their life together is blissfully normal, a patchwork of swimming lessons, gymnastics practices, ballet recitals, trips to the park, play-dates, birthday parties and sleep-deprived nights.

“The kids and moms I’m around every day, they aren’t really sports fans,” Lobo said. “We talk about raising kids. We exchange recipes on e-mail. They don’t see me as a basketball player. I’m just seen as the tall mom of Siobhan and Maeve.”

Lobo, who retired from the WNBA in 2003, hasn’t abandoned the basketball world. Once a week, she works on ESPN’s “Big Monday” telecasts of women’s basketball (tonight it’s Rutgers at Tennessee).

She takes the last flight out on Sunday – and the first flight home Tuesday.

“When Rebecca leaves, it’s almost like preparing for a six-month sea voyage,” Rushin said. “The kids are crying. It’s a long goodbye. But it’s a nice diversion and it keeps her around the game. No matter what, though, there’s never any confusion about her priority.”

Coming home. Being a mom.

The Fame Came Quickly

The other day, seeking to entertain his daughters, Rushin broke out an old tape of “Sesame Street.”

There was a 1997 version of Rebecca Lobo, wearing a New York Liberty uniform, issuing helpful reminders.

There are two O’s in Lobo. The basketball is shaped like an O. The hoop is shaped like an O. Somewhere in the spelling lesson, Lobo played basketball against Big Bird.

“Siobhan is watching, but she doesn’t see it as unusual in the least,” Rushin said. “Sure, there’s Mommy going one-on-one with Big Bird. Of course. Happens all the time.”

In the former life of Rebecca Lobo, things like that did happen all the time.

She was accustomed to people gawking, especially when she sprang to 6-feet-tall in the sixth grade.

But somewhere between her prep career at Southwick-Tolland Regional High School (where she scored 2,710 points, a Massachusetts record that still stands) and her senior season at Connecticut (when the Huskies finished 35-0 and became media darlings), things changed.

“We [UConn players] went to a mall before and nobody would notice,” Lobo said. “All of a sudden, people are staring at us. People want our autographs. It was odd.

“Something about our team just struck a chord. The Northeast media picked up on it. Most of us were kind of uncomfortable with it all, but I think we handled it well. It was this whole new world that opened up, and it happened overnight.”

Lobo was front and center.

She went from UConn’s unbeaten season to the 1996 Olympic women’s Dream Team to the 1997 inaugural season of the WNBA – with hardly a break.

“I think Rebecca is genuine and grounded, so she handled all the attention with grace,” Lobo’s mother said. “But I do remember her saying all the time, ‘You know, the real heroes in this world are working quietly in labs, curing diseases, or fighting overseas. I put a ball through a hoop. What’s the big deal?’

“Even now, people tell me, ‘I saw Rebecca at the grocery store the other day!’ And they said it with such a gasp, as if they can’t believe she would actually go grocery shopping. They marvel at seeing her. The thing I’ve observed is, almost invariably, she always has time for people, even the ones she has never met.”

She Doesn’t Miss Basketball

In 2001, Lobo was coming off two seasons of inactivity with the Liberty, after twice blowing out her ACL. Somewhere during the interminable exercise-bike time, she spotted a Sports Illustrated column, which she believed took a cheap shot at the WNBA.

One night at a New York bar, she met the infamous writer, Steve Rushin.

Lobo: “You wrote that? How many WNBA games have you attended to make such a judgment?”

Rushin (sheepishly): “I’ve never been to a women’s basketball game in my life.”

Lobo invited Rushin to an upcoming Liberty game at the Garden.

“Less than two years later,” Rushin said, “we were getting married.”

It coincided with Lobo’s examination of her fast-forward life. She wanted a family. For the first time in nearly two decades, she didn’t want basketball. So when her Connecticut Sun team was eliminated from the 2003 WNBA playoffs, after shedding tears in the losing locker room, she followed through on unspoken plans to retire.

“I don’t miss it, and I haven’t missed it, not once,” Lobo said. “I like going to a basketball game and not caring who wins. I like not having to revolve everything around basketball.

“My last season, I went with Steve to a party on the Fourth of July. Everybody was eating hamburgers and hot dogs, drinking cold beer. I had a bottle of water because I was playing that night. And I was thinking, ‘You know, I sure would like to have a hamburger and cold beer.’ Sometimes, the simple things are the best things.”

A few weeks ago, the kids couldn’t sleep (again). Rushin, awakened by the noise, stumbled to the family room and turned on the television.

“It was like 2 o’clock in the morning and I think it was Channel 139 on the cable,” he said. “It was a repeat of the sitcom ‘Martin.’ And sure enough, there’s Rebecca.”

Lobo, Dawn Staley and Sheryl Swoopes – in Olympic uniforms – were playing three-on-three against Martin Lawrence and two of his pals.

Rushin laughed to himself, thinking about the woman in the other room, the one trying to cope, the one attempting to settle their children.

Once, she was as recognizable as any women’s basketball athlete. Now she’s just Rebecca – you know, Steve’s wife, Mommy to Siobhan and Maeve.

Refreshingly normal.

Even though a part of her – the part that made women’s basketball history for UConn and beyond – still belongs to the world.

HOW I GOT STARTED

Dreams Within Reach

As Tampa prepares to host the Women’s Final Four in April, The Tampa Tribune will talk to notable players and coaches about how they began in the sport. Today, it’s Rebecca Lobo, who was consensus National Player of the Year when her Connecticut Huskies won the national championship in 1995.

“My mother always told me I could be anything I wanted. One day, I told her, ‘I want to play in the NFL.’ And she said, ‘Well, anything but that.’ In the third grade, I even said I was going to become the first girl to play for the Boston Celtics. I wrote that in a letter to Red Auerbach.

“I guess the point is I did have big dreams. And the idea of me being able to achieve anything was reinforced.

“We had a hoop up in our gravel driveway. We lived in the middle of nowhere, so it wasn’t like there were a bunch of kids around for a pickup game. A lot of times, I was alone, just dribbling and shooting.

“I was pretending I was passing to Larry Bird or I was pretending I was shooting off a pass from Larry Bird. That’s what I remember most about basketball. Being out there by myself, working on my game, imagining what I could be.”

Joey Johnston