By JOEY JOHNSTON

Tribune Staff Writer

(c) Tampa Bay Times Originally published: Oct. 1, 2010

Forty years have passed.

Yet time has stood still.

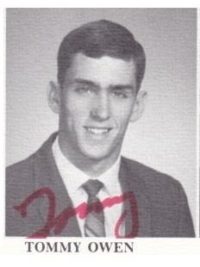

Lives were altered forever, but for friends of Tommy Owen, once an all-everything athlete from King High School, some things haven’t changed.

“We’re all getting close to retirement age, but our Tommy will always be young,” said Bobby Knight, a former teammate in football and baseball. “The guys still want to be just like him. The girls still want to be with him. He was one of those rare, special people you meet. That’s who he will always be.”

Had he lived, Owen would be 60, probably married with children. He might even be a grandfather. Odds are, he would still be making a difference.

On Oct. 2, 1970, Owen, a junior football player at Wichita State University, was traveling with his teammates on a Martin 404 twin-engine aircraft that was headed to Logan, Utah, for a game against Utah State.

But because of a change in the flight plan — and a miscalculation by the pilot, who took a scenic route because one of the players asked to fly over Loveland Pass — the plane flew into a box canyon near a ski resort area in Silver Plume, Colo.

It couldn’t gain altitude and crashed into the side of a mountain, killing Owen, 13 teammates and 17 others, including two Wichita State boosters who had won seats on the flight in a fundraising contest.

Owen was 20.

The trauma reverberated throughout Temple Terrace.

“Our family was never the same,” said Ladye Daniels, Tommy’s older sister.

Ten days ago, Wichita State held a 40-year memorial for the survivors and family members of those who died. Daniels reluctantly made plans to take her mother, Mary Owen, but worried about the emotional journey. It actually was therapeutic.

“We were reminded of how many people loved Tommy,” said Mary Owen, who often woke up in the middle of the night, sobbing and grieving, in the year after the accident. “But I already knew that.”

Tommy was a football, baseball and basketball star. He was president of the Key Club, a member of the National Honor Society and recipient of the Principal’s Award. His classmates voted him “Best All-Around” as a senior.

His natural charisma and low-key confidence, mixed with humility, translated to Wichita State, where he was beginning to realize his football dreams.

After the crash, cornerback Johnny Taylor escaped from the plane, but he was scarred badly by the fire. He was transported to a Dallas burn unit. When he first stirred, Taylor whispered a question:

“Did Tommy make it?”

A few weeks later, Taylor died.

“Why does this happen to a guy like Tommy Owen?” said Charlie Harrington, who was Tommy’s roommate at Wichita State. “He had so much to give.”

*******

Everyone remembers where they were on that Friday afternoon.

Mary Owen was playing bridge when the telephone rang.

Daniels, a rookie elementary-school teacher, was doing laundry in her apartment when her mother called in distress.

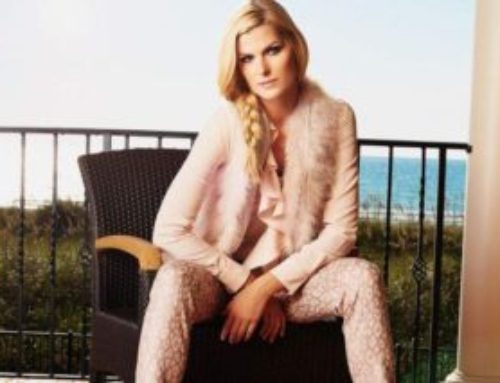

Susan Owen, Tommy’s younger sister and a King senior, was working a part-time job when she heard a radio news flash. When her legs began to wobble, she hurried home.

Bobby Starford, a friend since the third grade, was trying to nap. His mother was watching “The Match Game” in the family room. He blinked to attention after hearing the startling news bulletin.

Knight, the former teammate, stared at the television in stunned silence. Knight was engaged to be married. He had asked Tommy and another friend to serve as co-best men.

Wichita State student Sharon George, who developed an immediate crush when she met Tommy, was driving near campus when a radio newsman interrupted programming.

“There were so many people assembling near the athletic offices, they finally took us all in this room,” said George, who works in human resources at a Wichita hospital. “We waited for such a long time. They finally passed out a list of names — the people who survived and the people who didn’t. I still have that piece of paper.”

At the Owen home in Temple Terrace, the news was excruciatingly slow in coming.

“We kept waiting for a phone call, hoping it was Tommy saying, ‘I’m OK,'” said Daniels, the older sister. “The call never came.”

“I went home and slept by the phone in the dining room, just waiting,” said Starford, the longtime friend.

“We were operating in shock mode,” said Susan Owen, the younger sister. “I think it was midnight when they called to say Tommy didn’t make it. I remember standing on our front porch, kind of dazed, staring out into the night.”

*****

Why did it have to be Tommy? For 40 years, his friends have wondered.

“Right after the accident, I would look for Tommy’s face in a crowd, whether it was a sporting event or walking through an airport,” said Knight, the longtime friend and pallbearer at the funeral, who now is a sales consultant. “I somehow believed I would see him if I looked hard enough, almost like he didn’t really die in the crash.

“Maybe he walked off the other side of the mountain. Maybe he got a concussion and took on a whole new identity. Maybe it had all been this big mistake. Somewhere in there, I stopped looking.”

Starford, who is director of operations for a Toyota dealership in the Atlanta area, lost touch with the Owen family over time. A few years ago, he felt compelled to write them a letter, detailing how much Tommy meant to his life.

“I never forgot the guy,” Starford said. “We grew up together, but I wasn’t half the person Tommy was. I have a daughter. If I ever would’ve had a son to grow up to be like Tommy Owen, I would’ve been the happiest person in the world. I wanted Tommy’s mom and dad to know that. He could’ve been anything he wanted to be.”

Mostly, Tommy wanted to be a football player.

At Wichita State, Tommy played wide receiver and wingback, a man of perpetual motion who compensated for his smallish size (5-foot-10, 170 pounds). The week before the crash, Tommy made a brilliant catch — “one of the best I’ve ever seen,” Harrington said — and a photo of it made the newspapers.

So Tommy was on a high going to Utah State. Harrington, meanwhile, was on a low, having been demoted to backup defensive lineman. That’s why he rode on the other plane, which carried the non-starting players. The demotion saved his life.

When Harrington’s plane landed in Logan, Utah, he recalls, team members were taken to a chapel and informed about the crash. Tommy remains as Harrington’s roommate. For all these years, he has displayed Tommy’s photo in his bedroom bookcase.

“He’s maybe the finest person I’ve ever known, and I’m not sure if he ever did anything really wrong,” said Harrington, who named his daughter Toby because it sounded similar to Tommy’s initials: T.B.O.

When Harrington returned from Utah to the dorm room, Tommy’s belongings had been packed for the trip home. He noticed “Oct. 21” highlighted on Tommy’s desk calendar — his mother’s birthday. For years, Tommy begged his mother to stop smoking. After the accident, she quit cold turkey. She did it for Tommy.

In 1971, the Owen family received a camellia bush in memory of Tommy. Since then, it has been outside their home, usually producing about 30 pink blooms every winter. The blooms are cut and floated in a bowl as a reminder.

There is an endowed scholarship in Tommy’s name at Wichita State, which continued its football season two weeks after the crash, when the freshman team went to Arkansas and lost 60-0. All game long, Razorback fans cheered for Wichita State. In 1986, citing financial hardships, Wichita State dropped football.

But memories remain, particularly of the players who never came home.

*****

By all accounts, the father, Thomas Braden Owen Sr., was a man’s man.

At Vanderbilt University, he was elected captain in two sports and earned 11 varsity letters. He was a Marine during World War II, earning a Bronze Star and Purple Heart in Okinawa, Japan. He was a high school teacher and football coach in his native Nashville before the family moved to Tampa, then built a home along the golf course in Temple Terrace during the late 1950s. That’s when he began a drywall construction business.

The father and son were inseparable. In a quaint, sweet way, Tommy’s biggest hero was his father. The father subtly reminded his son about working hard, treating people right and always remaining humble.

“I had a great father,” said Knight, Tommy’s boyhood friend. “But I always thought if my dad hadn’t been around, I’d want Mr. Owen to be my father.”

On Oct. 2, 1970, the father had not heard the news when he arrived home. His oldest daughter told him: “One of the planes has gone down.”

“Oh, no,” he said softly.

The father, who positively identified his son’s body when it was returned to Tampa, tried to be strong for everyone. Harrington, who was on the second plane, had never seen a larger funeral. What he remembers most is Tommy’s father trying to comfort him.

In the years that followed, the father sometimes was spotted silently watching a football game at home, his eyes hollow and reddened, his mind a million miles away.

Jack Suarez, one of Tommy’s boyhood friends, went years without seeing the father until returning to Temple Terrace for the funeral of a mutual acquaintance. They talked for a long while. Suarez finally worked up the nerve to ask the father how he got over Tommy’s death.

“I never did,” the father said.

*****

With approval from the Hillsborough County school district, the family established the Tommy Owen Award in 1971. For 28 years, it was the only award given at King’s graduation, presented to a senior with character, scholarship and athletic ability.

In 1999, King Principal Richard Bartels decided to move the Tommy Owen Award presentation to the school’s Senior Awards Night, lumping it with other honors. The family wanted to maintain tradition and keep it on graduation night. Back and forth went the correspondence. Finally, the family, which provided the trophy but had no say in selecting the winner, decided to discontinue the award.

It wounded the ever-stoic father, who died at age 88 in 2008.

Dick O’Brien, Tommy’s head football coach at King, still can’t believe that Tommy’s No. 1 jersey, retired one week after the crash in 1970, was removed from the school’s trophy case for something more modern. Several times in the past decade, the No. 1 jersey has been worn at King.

“I guess King has forgotten,” said O’Brien, 72, now retired in North Carolina. “Well, he’s still a special person in my life. I never forgot that kid.”

This month, King High will hold its 50th anniversary celebration with hundreds of alumni returning for a weekend of events. There is a groundswell of interest in reviving the Tommy Owen Award and perhaps re-retiring his No. 1 jersey.

“I wanted to be Tommy Owen when I grew up,” said David McPhillips, a sophomore football player when Tommy was a senior. “At King, he was the best person we ever had.”

In a few weeks, the King alumni will return, a bit older, perhaps heavier, missing some hair, maybe lacking that old idealism. If they are of a certain age, the stories inevitably will revolve around one guy.

Thomas Braden Owen Jr.

He never changes. He’s still the best athlete, pound for pound, that anyone at King has seen. He’s still a friend, whether you were the homecoming queen or the girl everyone else ignored, whether you were the class president, the star player, a geek or a nerd.

He still looks back, with piercing eyes and a killer smile, from that senior photograph. It’s heartbreaking to remember all he was — and to imagine all he could have become.

Tommy Owen.

Gone too soon.

Forever young.